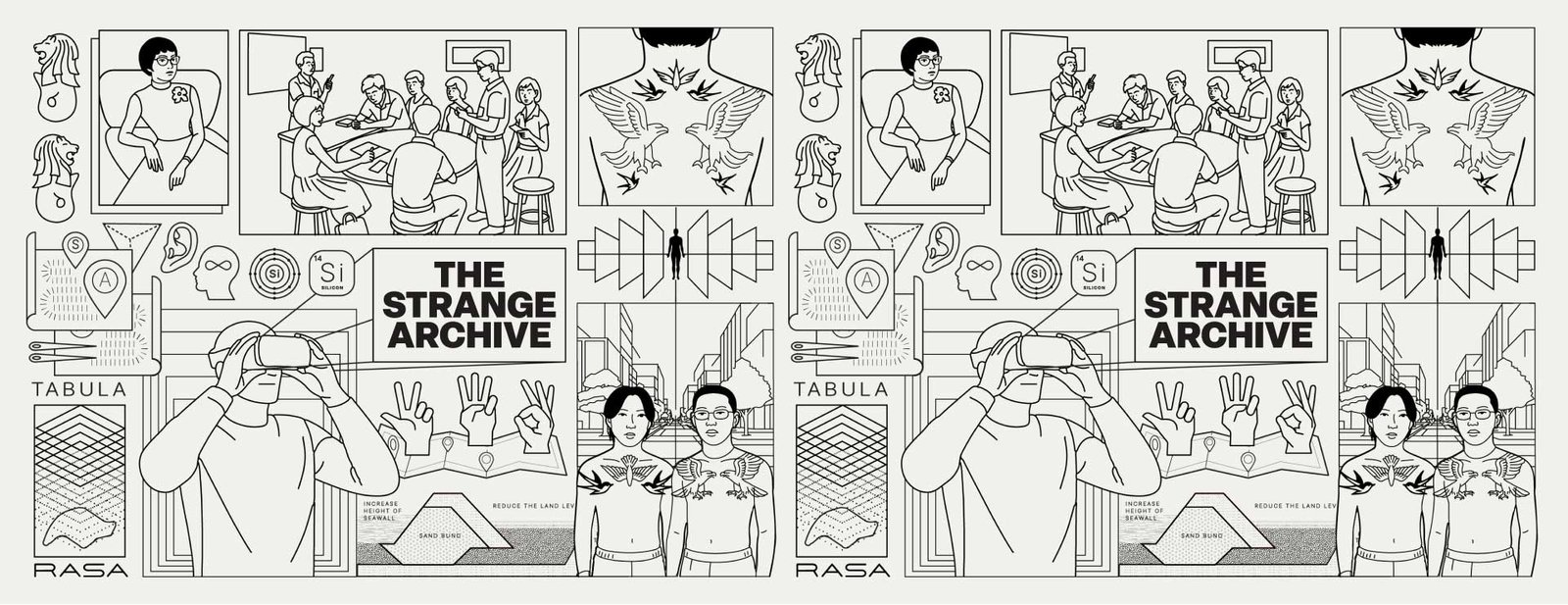

Exhibition

17 January – 1 February 2026 · Tanjong Pagar Distripark, 37 Keppel Road, #04-01D, Singapore 089064

Part of Singapore Art Week 2026

In Singapore, where archives are often tethered/pegged/tied to state narratives or institutional frames of memory, an official archive is expected to behave predictably and to hold history still. This exhibition begins from a somewhat different position. It proposes that the archive is restless, shifting, and fundamentally strange, and that this strangeness is not a deviation to be corrected but a method for learning how to see again, a way of destabilising what is known, making familiar histories feel uncanny, and opening new vocabularies for ground, identity, and belonging.

Curatorial Statement

“To make strange” is to learn how to see anew. When the archive is approached through this sensibility, familiar stories begin to take on an uncanny presence, and previously overlooked omissions, errors, or inconsistencies acquire weight and consequence.

The Strange Archive treats the archive as a provisional and reflexive space shaped not only by care, continuity, and labour, but also by desire, silence, and the unresolved ambiguities that permeate every act of remembering. Forgotten stories, unrealised projects, and obscured memories return not as authoritative truths but as fragments that invite re-reading, mis-reading, and lingering.

The exhibition is situated within the industrial corridors of Tanjong Pagar Distripark, a place defined by movement, labour, arrival, departure, and the circulation of goods. This setting mirrors the archive as something perpetually in motion. Pierre Nora has suggested that memory becomes designed the moment it ceases to be lived directly, leaving behind monuments, museums, and official histories as its traces. In contrast, The Strange Archive resists closure. It keeps the archive open as something unfinished and intimate, a structure through which new encounters and interpretations may continue to emerge.

The spatial language of the exhibition draws upon Céline Condorelli’s notion of “support structures”, which treats architectural and material elements as active participants in meaning-making rather than as a neutral audience. Hinges, windows, lighting, soil, sand, charcoal, and the unevenness of the floor are not passive fixtures but collaborators in shaping how viewers encounter the works. Walls, floors, texts, sounds, and smells become supports for artworks and provocations, inviting audiences to move through a strange and out-of-sorts library of oral, aural, tactile, atmospheric, and visual registers of memory. These materials underscore the fact that archives are constructed from things that deteriorate, erode, and shift over time, and they remind us that no archive is ever complete nor entirely truthful.

EXHIBITION DESIGNER’S NOTE

This archive is a room.

Read a room!

No! Write a room.

To write a room is to decide:

- its margins

- it’s lineweight*

- Its rulings

The table is an instrument with which we can write a room.

A pill-shaped table with ten people in suits – a boardroom

A table with two people in love – a date

A table with one person and a laptop – man at work

//

The Table

I am an archive of this tiny archive.

Remembering is not the opposite of forgetting but its lining.**

Within my edges I hang newspapers, notes from an old archive.

Between my seams I hold on to pictures of old friends.

On my surface lay objects – seed archives, a dossier on life, here.

I am the frame from which the archive is seen.

I am a line, weighted. Lean in!

I am a liminal instrument (or a paradox?) –

I separate and bring together; I can be a beginning or an end.

History is in order. Memory is a stream of consciousness.

Remembering is memory rewritten.*

//

Footnote:

*Lineweight is the thickness of a line.

**Lines borrowed from Chris Marker’s essay on Sans Soleil

***A boundary line is a linetype. Linetypes are visual properties on maps that are used to represent different physical or abstract features in a standardised way. They are typically a sequence of dashes, dots and spaces, which make the map easier to read. A boundary line is a legally agreed-upon demarcation separating the territories. It be physical or imaginary. These lines, also called borders, in some contexts establish a nation’s territorial limits and jurisdiction, controlling movement and resources.

Part of

Supported by